My healing from war story

My name is Donna Gallers, and I’m a holistic healer, writer, and artist. I’ve lived in New York City most of my life, but I also ride horses and spend a lot of time in nature. I’ve survived and continue to heal from Lyme Disease and chronic illness. And, I’m healing from war.

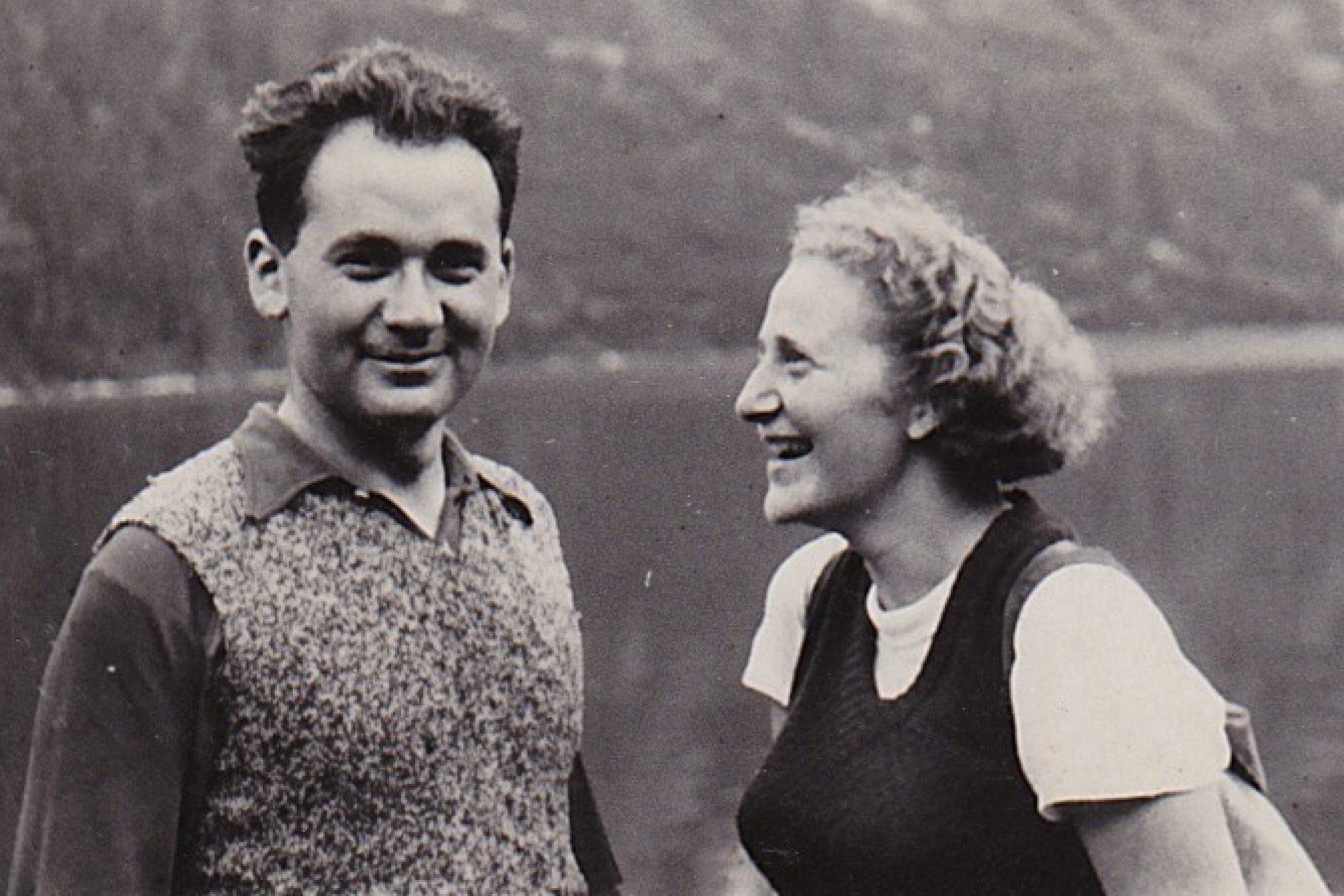

The legacy of war has been with me all my life. I am the grandchild of Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Warsaw. My mother was conceived during their months-long escape from Europe and born after they made it to the United States.

I grew up in the Bronx, in a close-knit community of Holocaust survivors, most of whom were Yiddish-speaking Bundists–members of the Jewish socialist movement in Poland. Even after the war, this group remained active in promoting fairness and equality in the world at large. They sought to preserve Jewish identity through the Yiddish language and secular, culturally-based activities.

My family never belonged to a synagogue, yet we devotedly celebrated all the Jewish holidays with Yiddish songs, plays, and secular rituals. I learned Yiddish at home and at Workmen’s Circle schools, and spent summers at the Bundist-run Camp Hemshekh, where each day we attended a khavershaft farzamlung (friendship meeting) to hear the news of the world and sing the rousing youth anthem, Mir kumen on! (Here we come!).

The Yiddish word hemshekh means “continuity,” and indeed, my childhood world encapsulated the zeitgeist of my grandparents’ lives before the war: the close friendships, Yiddish culture, and what seemed like a joyful struggle to make the world a more just and beautiful place. The survivors were fiercely committed to one another and deeply engaged in the world around them. They didn’t talk much about the traumas of the war years with their children or grandchildren.

And yet, the same continuity that brought me inspiring values and models of human connection also transmitted the unspeakable losses. The Holocaust was always on in the background, like a radio with the volume down. We called it der khurbn–the destruction. As a young person, I was fascinated by books about people hiding in attics or underground, families sent to Siberian labor camps, and accounts of the concentration camps themselves. I also found myself inexplicably drawn to stories about children facing fatal illnesses–deadly experiences they couldn’t escape from–which I’m sure was related.

Throughout my childhood I participated in our community’s annual Warsaw Ghetto Uprising memorial, the only time I saw the adults around me publicly show their grief. The heroes and martyrs of the Uprising, the partisans in the forests, the Jewish couriers living in secret outside the Ghetto walls– these were their family and friends, part of a vanquished world they’d never see again.

Much of my identity has revolved around this unique upbringing, at once a powerful paradigm of resilience and an inextricable set of gaps and silences that left me with lasting confusion about my safety, value, and belonging in the world.

One of the legacies of genocide is the feeling of dispensability, of not mattering, and of needing to contort or hide one’s true self in order to be accepted, tolerated or welcomed. As a descendent of survivors, it’s hard for me to feel secure in the world. This feeling is often coupled with the sense that whatever I accomplish is never enough–that I must somehow make their survival worth it. In trying to create and fulfill a vision for my own life, I wrestle with the impossibility of ever making up for all the hopes and dreams that were lost.

The relentlessly missing information about my ancestors has become the fabric of my dreams, a darkness I continually reach for, hoping to uncover the remembrances that feel like mine but aren’t. I live with phantom memories of people I’ve never met and places I’ve never been, and have spent much of my life imagining the life I may have lived if not for the total erasure of that world and that possibility.

I see my basically comfortable, totally American life– my choices, challenges, joys and successes– through the frame of the Holocaust’s aftermath. This has been a limiting vision and one I’ve always struggled with. It makes it more difficult to face growing older, contending with health challenges, or having limited financial resources, which we’re told (in the U.S. especially) are a measure of success and security. It makes it harder to think clearly about current events.

At the end of the day, growing up in the shadow of der khurbn/the destruction has been both a burden and a gift. For all the undeserving fears, unasked-for responsibility, and ever-looming grief it has left me with, I also feel grateful for my special link to a precious circle of comrades who, although scattered across the globe after their homes and families were turned to ash, dared not only to survive, but to keep fighting for a world in which everyone gets to thrive.

(For more on my family’s story, click here.)