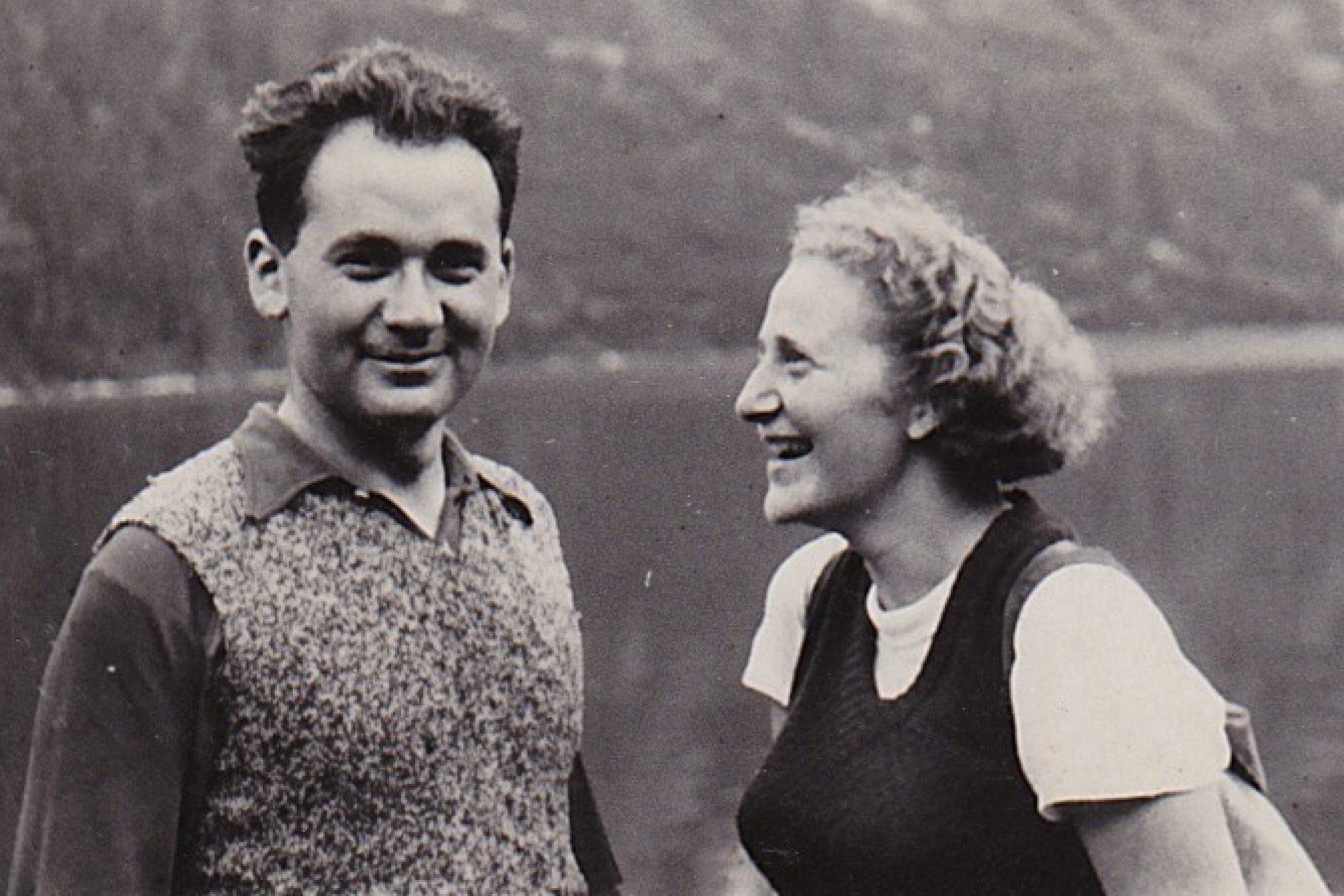

My maternal grandparents, Brucha (née Zalcman) and Emanuel Patt (known as Monye) met in Warsaw as youth leaders in the Jewish socialist movement, known as the Bund. That’s them in the header photo, on a hiking trip in 1933. Monye attended medical school in Warsaw and became a physician, and they got married. Soon after the Nazi occupation of Poland in 1939, they fled Warsaw and began a nearly year-long journey as refugees. They were 24 and 27 years old, respectively.

Brucha and Monye escaped Warsaw shortly before all the city’s Jews were imprisoned in the area that became the Warsaw Ghetto. For months, they traveled across Eastern Europe, sometimes with false identity papers, before finally reaching Japan using exit visas they’d received from Sempo Sughihara, the Japanese consul in Lithuania. (Sugihara single-handedly wrote thousands of visas for Jewish refugees to leave Europe before his own government removed him from his post.)

Monye’s father, Jacob Pat (my great-grandfather), was a prominent Bundist leader and educator who was visiting New York on business in the late 1930s when the war broke out in Europe. Apparently on a wanted list in Poland, he remained in the United States. Through his connections and persistence he helped a group of over 100 fellow Bundists (Monye and Brucha among them) get permission to come to the U.S. as political refugees at a time when few Jews were being let in at all.

My grandparents sailed from Japan to the U.S. in late 1940 on a Japanese ocean liner called the Heian Maru, arrived in Seattle, and then traveled by train to New York. My grandmother was pregnant when they arrived. My mother, Rebecca, was born a few months later, her parents thrilled that she was an American citizen.

Knowing of the devastation in Europe and unable to watch from afar, my grandfather Monye joined the U.S. Army in 1944 and went overseas, serving in France and Germany. As captain of a medical unit, he was among the troops that entered the concentration camp Dachau after liberation. There, he photographed the horrors he witnessed and wrote detailed reports for the Jewish press. He also exchanged dozens of personal letters in English and Yiddish with my grandmother Brucha, all which I have today.

The letters offer a powerful picture of their mindset at the time. They’re filled with mundane details and charming descriptions of their precocious daughter (my mom), side-by-side with intimations of the horror, anger, grief and anxiety they experienced imagining the fates of Europe’s Jews, among them so many of their family and friends. They knew most had suffered tremendously and probably lost their lives, and they would spend months and years waiting for news.

I’m not sure if they ever found out exactly what happened to their families. Brucha lost her parents, several siblings, and who knows how many cousins, nephews, and others from Warsaw. Most were probably murdered in the Treblinka death camp. Monye lost his aunts and extended family, who had lived in Bialystok. Many of their friends, neighbors and fellow Bundists who stayed in Warsaw had participated in the underground resistance and the 1942 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; most died. Two generations later, I don’t know the names or biographical details of most of my ancestors because of this erasure of history.

After the war, my grandparents were active in helping other survivors resettle and rebuild their lives. Their home in the Bronx became a stopping place for a number of survivors who’d arrived in New York after spending time in displaced persons camps or refugee communities in Sweden or Shanghai. Several children of survivors have told me that one of their first memories of arriving in the U.S. was a visit with Dr. Patt to make sure they were healthy.

My great-grandfather Jacob Pat continued his work as a Jewish labor leader and writer during the post-war years. In 1946 he traveled with a delegation from UNRRA (the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) to Poland, touring the country for two months interviewing Jewish Holocaust survivors. The result was a book in Yiddish called (in the published English translation) Ashes and Fire– a detailed, wrenching and personal testimony about Polish Jewish victims and survivors of genocide.

Along with my great-grandfather, both of my grandparents remained involved with Jewish culture and social justice movements for the rest of their lives. My mother Rebecca and her brother Avram, born in 1941 and 1950, respectively, were instilled with these values as well as the hurts and terrors of the Holocaust. They passed on both to their children– me and my generation.