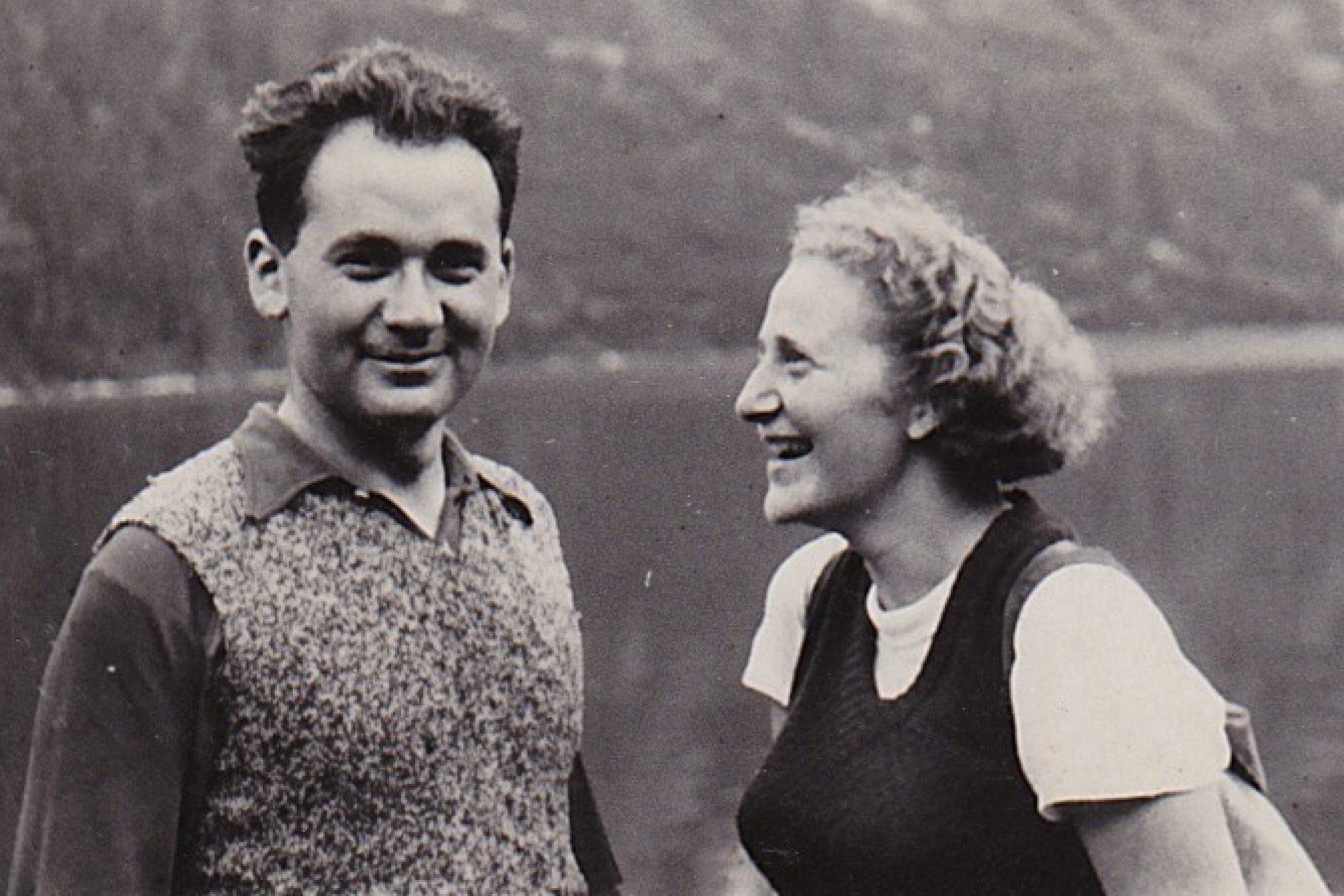

These are truly tumultuous times. Many are making comparisons to other times in history, in particular to the Second World War. I’ve been immersed in the ripple effect of that war all my life. My grandparents (and my mother, in utero) came to the U.S. as Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Poland in late 1940 and watched in desperation as the world they knew and loved (and fought to improve as members of the Jewish Labor Bund) was annihilated.

Between 1942 and 1946, my grandfather, Emanuel Patt (known as Monye), then in his early thirties, wrote a series of letters in Yiddish to his toddler daughter, Rifkeleh (Rebecca—my mother). In them, he shared his thoughts about the harrowing nature of the world they lived in and the brighter world he had dreamed of and worked for all his life.

The letters offer a portrait of both immeasurable loss and tenacious hopefulness—a determination not to give up faith in humanity and our power to turn things around. And they’re unique in having been written while those wartime events were happening, not in retrospect.

My grandfather saved all the letters, typed them up and gave them to Rifkeleh in 1958, on the occasion of her high school graduation, prefaced by a new letter offering them as a key to her foundation, roots and family as she made the transition to adulthood. She, in turn, saved and translated them to English and gave them to me when I graduated high school in 1987. They’ve informed how I understand the world ever since.

I’ve decided to begin publishing and sharing the “Letters to Rifkeleh” in my blog. Here, I’m including the full text of this 1943 letter to show not only my grandfather’s philosophical thoughts and lyrical writing but his full humanness as a young, immigrant father and family man.

November 23, 1943

November 23, 1943

My dearest nakhesdik [pleasant] little daughter:

Today you become 2 ½ years old. A big girl already. Mama went out for a while and left you in the apartment. So, you’re lying in your room, in your bed, and you’re sleeping. Have a good, sweet sleep!

Rifkeleh! When you grow up and will be able to read what your father is now writing, there will be a new, very different world than what we have now. Who knows if you’ll be able to understand your Papa’s thoughts on a November night in 1943?

Where is the world going? There is no one who has an answer.

But the world is not moving in the direction that your Papa and Mama wanted.

Your mother and father sold their souls to a dream. A dream of a beautiful world. The joys of wealth didn’t appeal to them and leave them cold. They themselves can manage with the minimum. But they have with passion and devotion dedicated their belief in justice and freedom and equality. Many names have been given to their beliefs. It seems to your father there here are the two critical things: that which is immortal in the history of humanity – the striving to self-betterment and advancement, that which is labeled humanism; and freedom, the soil without which humanity can’t exist, the air with which humanism breathes.

But these days there is no great need for these. The world has become a shelf of wares with which one trades. Peoples, countries are leftover scraps of fabric or cans of herring which with the big wholesalers trade in their business. And the individual person – the greatest and most important – is only a thread n the scrap of fabric or one of the pressed sardines

If only strength and physical power dominated – then it would even be tolerable. When the strength of a young hero manifests itself, it doesn’t necessarily have to be hooliganism. There is, after all, beauty in the powerful lifting and lowering of a hammer by a young, singing blacksmith! And this is also how it is in world politics. When a young nation begins to put a halt to destruction, begins building rainbow-bridges from the simple earth to the lofty sky – this is beautiful!

But today it is the power of cunning. It is the invincibility of cynicism.

If your father wasn’t such an incurable optimist, he would surely be coming to some very sad conclusions: we are the last of the Mohicans, Don Quixotes in a world that doesn’t understand what truth and purity mean.

But I want to believe that this is not true: that the elements of victory will wipe out all of today’s vile and common cow-trading. That the nations will delete all the accounts of this present time.

But I’m not certain about this. It could be – yes; and it could be – no.

But about one thing I am sure:

Just as the seasons of the year change, as Spring inevitably follows Winter, as surely will the dawn of humanism arrive, a time when ideas and ideals will rule the world; when words such as “truth” and “equality” will carry more weight than the grocer’s reckonings, when we will breathe freedom and not even be able to be satiated with enough brotherhood.

I promise you, my little girl, that when that time comes, and you and the youth of your generation will tear away the cobweb-covered windows and begin breathing the free air of humanity – then you will find your father and your mother, the incurable dreamers, by your side.

And it is our most fervent desire, our aim in life – to make you ready for that day.

If you will grow up and make these ideals part of your way of life – then this will be your mother and father’s greatest joy. If we will be unable to protect you and your soul becomes poisoned with the cynicism and nihilism of the times – then we will have failed in our task.

You are lying, little Rifkeleh, in your small bed. The golden curls fall down over your forehead. You sleep peacefully and your dream is of a little flower, a kitten, the little piglet that cries because its mother went away. You don’t know anything about your father’s thoughts and the grand philosophies he spins about you.

So sleep sweetly, our comfort and hope!

Your Papa

I stood on Nowolipie Street where my grandmother’s family lived. Not one building remains from before the war, but I pocketed a tiny chunk of what I like to think may be rubble from that time. I felt a sense of peace in the quiet residential neighborhood that’s there today.

I stood on Nowolipie Street where my grandmother’s family lived. Not one building remains from before the war, but I pocketed a tiny chunk of what I like to think may be rubble from that time. I felt a sense of peace in the quiet residential neighborhood that’s there today. And finally, yes, I went to the death camps. Auschwitz, with it’s orderly brick buildings and neat sidewalks, and Birkenau, with its barren blocks of wooden bunkers – the concentration camp I’d always imagined. I walked through the famous “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate to be surrounded by barbed wire fences. I saw jumbles of shoes, piles of pots and pans, a mountain of shorn women’s hair. I stepped inside a gas chamber. I stood just a few feet from the ovens. I walked by the pond where the Nazis used to dump the ashes. I wept. I was furious. I felt numb.

And finally, yes, I went to the death camps. Auschwitz, with it’s orderly brick buildings and neat sidewalks, and Birkenau, with its barren blocks of wooden bunkers – the concentration camp I’d always imagined. I walked through the famous “Arbeit Macht Frei” gate to be surrounded by barbed wire fences. I saw jumbles of shoes, piles of pots and pans, a mountain of shorn women’s hair. I stepped inside a gas chamber. I stood just a few feet from the ovens. I walked by the pond where the Nazis used to dump the ashes. I wept. I was furious. I felt numb.